"I am not prepared just now to say to what extent I believe in a physical hell in the next world, but a sulphur mine in Sicily is about the nearest thing to hell that I expect to see in this life." Excerpt from the book, The Man Farthest Down, by Booker T. Washington, published 1912

What prompted Booker T. Washington, a former African American slave, to write this?

They were known as the carusi, the mine boys. A poor Sicilian family would bind a child to a miner or picconiero, in effect selling their child to work a life of servitude in exchange for a loan that couldn’t ever possibly be repaid. Boys as young as six years of age worked in unsafe, horrid conditions carrying bags of sulfur from deep underground to the surface. Because of the hot temperatures, oftentimes, they were naked or near-naked. Covered in dust, a child might carry a bag weighing in excess of fifty pounds to the surface. His reward was to repeat the process over and over, eight to ten hours a day, six days a week—sometimes for the rest of his life. Although laws were passed in the 1900s to set minimum ages for children, for some it was too late.

Sulfur mining operations commenced in Cozzo Disi circa 1839. In the nineteenth century, Sicily had a near monopoly on the western world’s sulfur supply. It was a valuable commodity with many uses, not the least of which was in the production of gun powder.

Sulfur used to be called brimstone because it was thought to feed the fires of hell. Not a bad analogy when one stops to think about the ravaging destruction the forced labor had on the bodies of the carusi. Long term exposure led to partial or complete loss of vision and deformed backs, shoulders and knees.

In Leaving Marinella, Saverio’s fears about his son being forced to work in a mine would not have been at all untrue or exaggerated. It was not uncommon for some to work their whole lives as carusi—living, eating, sleeping, and dying in or near the mines from accidents, tuberculosis, or pneumonia.

Although the mine is closed, this fading road sign serves as a reminder of what used to be.

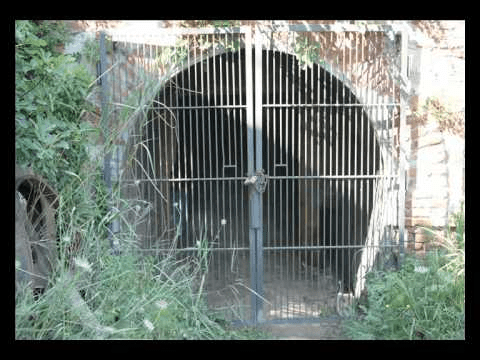

The abandoned empty shell of a place from the road is an eerie sight indeed. Standing at a fence meant to keep the public out, I couldn’t shake the palpable dreadful feeling that it also served to keep the horror locked in—because once upon a time, it was a sentence to hell for young boys.

When I closed my eyes, I thought I could almost hear the hundred-plus-years-old cries of pain seeping through the brick covering.

Operations ceased. Miniera Cozzo Disi (1839 – 1988). Rest in Peace.

Thanks scary will read in depth Carole DeLongwww.themousershouse.com

LikeLike